I was initially intrigued by Palm Beach Dramaworks’ (PBD) first-ever revival play TRYING by Joanna McClelland Glass because of its premise. It shows how people of extremely disparate backgrounds and generational experience can spar yet keep working together to where they eventually respect and even deeply care for one another. If an ailing, patrician 81-year-old former US attorney general and judge from a prestigious American family and a vigorous, determined non-Ivy-League educated young woman of 25 from a small Canadian prairie town (who’s hired as his secretary) can learn to get along, perhaps there’s still hope for the rest of us. Particularly in our contentious times.

So I totally get why PBD’s highly acclaimed producing artistic director William Hayes (who also directs the play, superbly) decided now was the time to remount their 2006-07 season offering of 2004’s surprise Off-Broadway’s hit. Hayes encapsulates “Trying” as being “about two people who learn to connect with each other despite their vast differences.” He was drawn to the play “because it’s about something that seems to be a lost skill these days: the art of communication.”

I was also drawn to the play because it’s based on a true story. The playwright had actually worked as a private secretary to esteemed Judge Francis Biddle during 1967/68, the last year of his life. He was renowned as a passionate civil rights advocate whose many civic-minded accomplishments include promoting FDR’s New Deal and being appointed by President Truman to serve as the American judge in post-WWII’s Nuremberg trials.

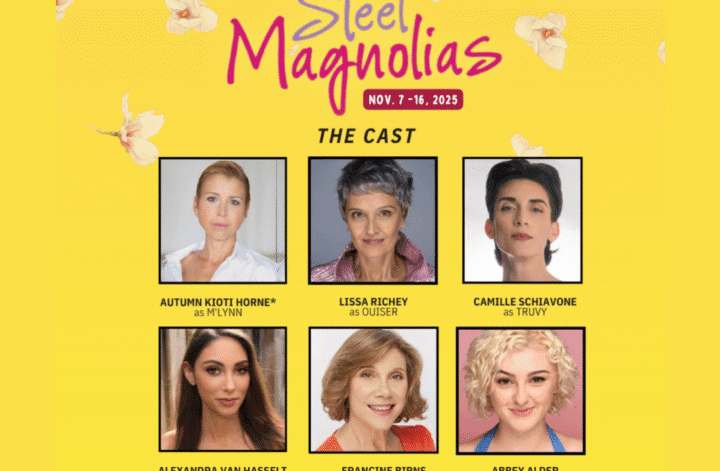

Kelly McCready and Dennis Creaghan star in PBD’s outstanding revival of TRYING byJoanna McClelland Glass. Playing now through June 9 in West Palm Beach. Photo by

Tim Stepien.

The term “trying” is used in various contexts throughout the play – as in trying to understand the other, to comply with their requests, to give respect. When Glass introduced her play, she wrote: “We spent our months ‘trying’ to negotiate and span our enormous differences of youth and age, of class and culture.” It wasn’t easy. Early on, Judge Biddle rebukes his secretary with: “You are the most trying person it was my misfortune to meet.”

The playwright took a few artistic liberties with her alter-ego’s character, Sarah Schorr, by casting her several years younger and in a differing marital situation. But I’m quite sure Judge Biddle is portrayed with admirable authenticity – including his curmudgeonly “old man” complaints, his snobbery, criticisms … even his proclivity to fight dirty. All the while sadly, though still humorously, aware of his fast approaching demise and surprising memory lapses. Still, up to the very end, he regales us with his incredible wit and wisdom, verbatim knowledge of great artistic and literary figures, and a fascinating past where he mingles with the rich and famous.

What I didn’t expect – and now admire most in the playwright – is how seamlessly she manages to weave an emotionally laden two-hander with illuminating historical incidents, quotes from respected literary figures, and the pathos of inevitable aging set against the unrelenting optimism of youth. All the while keeping – especially in the ongoing patter of the judge – a wry commentary about life’s many foibles and aggravations that had me laughing out loud!

Many of Biddle’s quotes, and some of Sarah’s, are so erudite, my theater partner plans on getting a copy of the script in order to read, and fully savor, the clever repartee. I also appreciated being educated in the history of the first half of twentieth century, an aspect of my schooling that was sorely lacking. And I’ll likely revisit poetry-loving Sarah’s favorites: Edna St. Vincent Millay and E. E. Cummings. Sadly, hooked as we are on Google search, I doubt many of us could even quote their favorite lines from literary giants, as these two did, so effortlessly.

All six scenes of the quick-moving two-hour-and-25-minute play (with one intermission) are set in Judge Biddle’s office – a reconstructed hayloft of an 1830 barn in Georgetown, DC. It houses a wealth of book cases, steel file cabinets, two desks (his, more massive and ornate, and the simpler secretary’s, with clacking typewriter). The classic wooden furnishings appear Edwardian and, for when the judge needs to rest (which is often), there’s a simple cot for lying down, as well.

Two tall windows in the rear reveal outdoor light, depending on the time of day; visible snowflakes fall during the blustery opening scene. There are also two electric heaters which only Judge Biddle may turn on and off because, as he repeatedly states, his former incompetent secretary said she’d shut them off for the night but turned them fully on instead, setting the place on fire and incurring the loss of many antiquarian books while “all the files went up in ashes.” His top-shelf books still reek of smoke.

Because PBD’s lovely theater is comfortably mid-sized and features stadium-height seating, everyone can enjoy a personal “up front” view of the exquisitely designed set by scenic designer Bert Scott and all the action. Scenes are clearly seen and heard due to lighting design by Addie Pawlick and sound design by Roger Arnold. Despite the voluminous dialog by incredible actors who instantly make you believe they ARE their characters, and never let up for a second, there’s also plenty of movement (or in the judge’s case, attempts at movement) as Sarah briskly paces to fetch her shorthand notebook, serve coffee, etc., that keep one’s eyes engaged throughout. Stage manager Suzanne Clement Jones did an excellent job and I can vouch that Sarah’s outfits by costume designer Brian O’Keefe are period authentic (as I recognized quite a few from my own early secretarial forays).

Kelly McCready (right) as Sarah points to Dennis Creaghan as Judge Francis Biddlewhen she finally lays down her law, refusing to be bullied any longer. Photo by Tim

Stepien.

Obviously, a dialog-rich, two-person play rests squarely on the talents of its actors and here (despite rave reviews for Off-Broadway’s 2004 premiere’s thespians) I can’t imagine anyone else in these roles. PBD’s longtime favorite Dennis Creaghan (over a dozen productions in the past 12 years), with an impressive outside career as well, was the perfect choice to play Judge Francis Biddle. He even looks the part, and dare I say, sounds like the judge!

Keeping up and shining on her own (just like in the story) is young Australian newcomer to Palm Beach (but with an impressive resume both in acting and as a writer/director) Kelly McCready in a pitch-perfect performance as Sarah. I’m especially impressed by her “pitch” after viewing a short PBD interview wherein the Australian native speaks in full Aussie accent. I wondered how that would translate to Sarah Schorr from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. But her North American diction was flawless.

The play opens to the song “Monday, Monday” by The Mamas & The Papas. An old- time radio sits on a shelf from where it broadcasts popular songs of the sixties to herald each scene change (offering a preview of what’s to come and/or a light, nostalgic reprieve from heavier action). The radio is also used to deliver headline news of the time – from November 1967 through June 1968 – an especially volatile period in our history.

We meet Judge Biddle after first hearing him clomp slowly up the stairs, bundled up for the snow and struggling to sit and remove his galoshes. Next to arrive (“too early,” he complains) is lighter-footed Sarah, equally bundled and cold. He refuses her help to turn on the electric heaters, not trusting her competence with these fire-prone devices, as aforementioned, and even complains that she’d arrived before 9 am for her first day (which he dreads, having gone through a long list of departing secretaries). We immediately get that he’s a crotchety character, but Sarah, who’d been forewarned and hired by his wife for her “spine,” is determined to not let his attitude get to her or keep her from performing her duties, which she “naggingly” keeps asking about, as he drones on with his litany of grievances. “I’m fairly certain this will be my last year,” he frequently observes. Adding, “The exit light is blinking over the door, and the door is ajar.”

The judge has heaps of correspondence to answer – both from his publisher asking for months’ late chapters of his memoir, and multiple others. Numerous Harry Truman biographers seek his personal expertise to fact check their manuscripts. As they go through the letters, we glean his personal views of history, including a lifelong regret that he hadn’t fought harder to stop the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War 11, proclaiming: “My urgent opposition to Japanese internment fell on deaf ears. Never again will I trust in the mythic cliché of ‘military necessity’.”

Much revered and irascible Judge Francis Biddle (Dennis Creaghan) stresses a point ashe gives dictation to his latest, youngest, secretary, Sarah Schorr (Kelly McCready).

Photo by Tim Stepien.